Computing for ocean environments

The ocean is one of the most unforgiving environments. Large swathes of the ocean remain unexplored due to its unpredictable weather patterns and limited communications.

Wim van Rees is the ABS Career Development Professor at MIT. He says that “the ocean is a fascinating ecosystem with a number of challenges like microplastics and algae blooms coral bleaching and rising temperatures.” “At the exact same time, there are many opportunities in the ocean — from aquaculture to energy harvesting to exploring the many sea creatures we don’t yet know.”

Van Rees is an ocean engineer and mechanical engineer who uses scientific computing to solve the ocean’s many problems and take advantage of its opportunities. These scientists are working to develop technologies that will allow us to better understand the oceans and the way organisms and humans can move in them.

Bio-inspired underwater devices

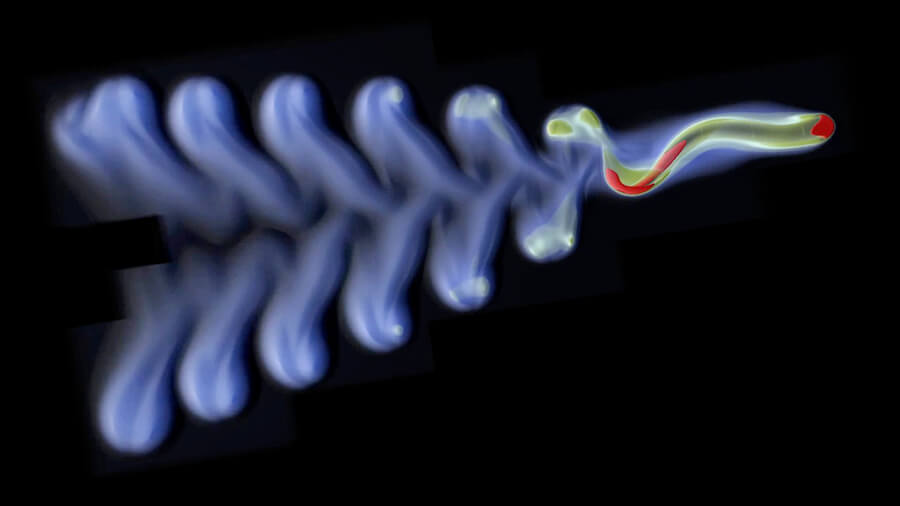

Fish dart through the water in a complex dance. Flexible fins move in currents of water and leave a trail of eddies behind.

Fish have complex internal muscles that allow them to adjust their fins and bodies. Van Rees explains that this allows fish to propel themselves in many other ways, far beyond the capabilities of any man-made vehicle in terms agility, maneuverability, or adaptability.

Van Rees says that we are now closer than ever to creating flexible and morphing fins for underwater robotics thanks to the advances in additive manufacturing, optimization techniques and machine learning. This makes it more important to understand the impact of soft fins on propulsion.

Van Rees and his colleagues are using numerical simulation methods to explore the design possibilities for underwater devices with increased freedom due to deformable fins that look fish-like.

These simulations allow the team to better understand the fluid-structure interaction of soft and flexible fins in fish. They are now able to understand how fin shape changes can affect swimming performance and harm. Van Rees adds that supercomputers can be used to solve the problem at the interface of the flow and structure by using precise numerical techniques and parallel implementations.

Van Rees hopes to create an automated design tool that will allow for the development of a new generation autonomous underwater devices by combining his simulation algorithms for flexible structures with optimization and machine-learning techniques. This tool can be used by engineers and designers to create underwater vehicles and robotic fins that adapt to their shapes in order to achieve their immediate operational goals.

Van Rees explains, “We can use optimization and AI to do an inverse design within the whole parameter space, create smart, adaptable device from scratch, and use precise individual simulations to identify physical principles that determine why one form performs better,”

Robotic vehicles using swarming algorithms

Michael Benjamin, Principal Research Scientist, wants to improve how vehicles navigate through water. Benjamin, then a postdoctoral researcher at MIT, launched an open-source project to develop an autonomous helm technology. This software has been used by companies such as Sea Machines and BAE/Riptide as well as Thales UK and Rolls Royce. It also uses a unique method of multi-objective optimizing. Benjamin’s PhD research led to the development of this optimization method. It allows a vehicle to choose its heading, speed and direction to meet multiple objectives simultaneously.

Benjamin is now developing obstacle-avoidance and swarming algorithms. These algorithms could allow dozens of uncrewed vehicles communicate with each other and explore a particular part of the ocean.

Benjamin is currently focusing on how to disperse autonomous vehicles across the ocean.

Let’s say you want to launch 50 vehicles into a portion of the Sea of Japan. Benjamin explains, “Is it more efficient to drop all 50 vehicles in one place or have a mothership drop them off at specific points within a particular area?”

His team has developed algorithms to answer this question. Each vehicle communicates its location periodically to other vehicles using swarming technology. Benjamin’s software allows these vehicles to spread in the best possible distribution for the area they are operating in.

The ability to avoid collisions is key to the success and safety of the swarming cars. Collision avoidance can be complicated by international maritime rules called COLREGS (or “Collision Regulations”), which determine which vehicles have the “right-of-way” to cross paths. This presents a unique challenge to Benjamin’s swarming algorithms.

The COLREGS were written with the goal of avoiding one contact. However, Benjamin’s swarming algorithm must account for multiple unpiloted vehicles trying not to collide with each other.

Benjamin and his team devised a multi-object optimization algorithm to rank specific maneuvers on a scale of zero to 100. One would indicate a collision while 100 would indicate that the vehicles have avoided collision completely.

Benjamin says that “our software is the only marine program where multi-objective optimization provides the core mathematical basis for decision making.”

Researchers like Benjamin and van Rees employ machine learning and multi-objective optimizing to solve the problem of vehicles traversing ocean environments. Pierre Lermusiaux at MIT, the Nam Pyo Uh Professor, uses machine learning to understand the ocean environment.

Improve ocean modeling and forecasts

Oceans are perhaps the most well-known example of a complex dynamical system. The ocean is a dynamic environment with fluid dynamics, weather patterns and climate change. It can be unpredictable at all times. Forecasting can be difficult due to the constantly changing ocean environment.

Although dynamical system models have been used by researchers to predict ocean environments, Lermusiaux points out that these models are not perfect.

When developing models, you can’t account every molecule in the ocean. Model resolution and accuracy are very limited, as well as ocean measurements. A model could have a data point for every 100m, every kilometer or, if you’re looking at climate models for the global ocean, one data point per 10 km. This can impact the accuracy of your predictions,” says Lermusiaux.

Abhinav Gupta, a graduate student, and Lermusiaux, a machine-learning framework have been developed to compensate for the low resolution and accuracy of these models. The algorithm can take a simple model of low resolution and fill in the gaps to create a complex model with high resolution.

Gupta & Lermusiaux have created a framework that learns from existing approximate models and introduces time delays to increase their predictive abilities.

Gupta says that things in nature don’t happen in a single moment. However, most prevalent models assume they do. “To make an approximate model more precise, the machine learning and data that you input into the equation must represent the effects past states have on future predictions.”

The “neural closing model” of the team, which accounts for these delays could lead to better predictions such as a Loop Current current hitting an oil rig at the Gulf of Mexico or the amount of phytoplankton present in a particular part of the ocean.

Researchers can unlock more mysteries of the ocean and find solutions to the many problems facing the oceans as computing technologies like Lermusiaux and Gupta continue to improve.